Blueprint for Brutality: Srebrenica's Lesson

30 years ago, 8000 Muslim men and boys were killed in eastern Bosnia. Those deaths were entirely predictable—and preventable.

Happy birthday dear Şenaycım!

A reminder that this is the last newsletter for the next few weeks! I’ll be back in August. 😎

Today’s newsletter is heavy—a far cry from the humor and sass many of you tell me that draws you to read Interruptrr. Hey, things are heavy now, what can I say? While I do try to keep things upbeat, I never want to be flippant or dumb things down. Just a disclaimer…. Also, it’s been a week, so apologies for any typos….

If you like the newsletter, please give it some love by hitting 🖤 above —and, please, share with others. If you ❤️ the newsletter, please become a paid subscriber.

On July 11, 1995, Bosnian Serb forces swept into Srebrenica, a town in eastern Bosnia that the UN had been “protecting.” General Ratko Mladić ordered his men to separate Muslim women from the men and boys, put them on board buses and drive them out of the area. He then ordered that the men and boys be rounded up. Dutch peacekeepers deployed to the area stood by and watched. Over the next five days Serbs executed nearly 8,000 of them—the worst mass killing in Europe since World War II.

Srebrenica was predictable—and preventable—had someone—anyone— stood up to stop Serbian aggression. That vacuum of resolve turned the massacre into a blueprint and license for atrocities to come—some that we are witnessing today.

The Srebrenica massacre was an extension of the violence the Serbs, Orthodox Christians, had inflicted upon Muslims and Catholic Croats since the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991. Formed in 1918, Yugoslavia comprised six enclaves: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia. In 1991, Slovenia and Croatia, the western most provinces, declared independence. Bosnia followed in the following year. Croatia and Bosnia both had sizable Serb populations, which Serb leader Slobodan Milosević maintained needed to be a part of a greater Serbia. From his perch in Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, he masterminded, along with Mladić and Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, a brutal campaign to reclaim territory from the newly independent countries and purge non-Serbs from it.

In her book, “A Problem From Hell,” Samatha Power notes that, at the start of the war, Bosnian Serbs began using force, intimidation, and violence towards Muslims and Croats— “rounding up non-Serbs, savagely beating them, and often executing them. Bosnian Serb units destroyed most cultural and religious sites in order to erase any memory of a Muslim or Croat presence in what they would call ‘Republika Srpska.’” They openly called their actions ethnic cleansing.

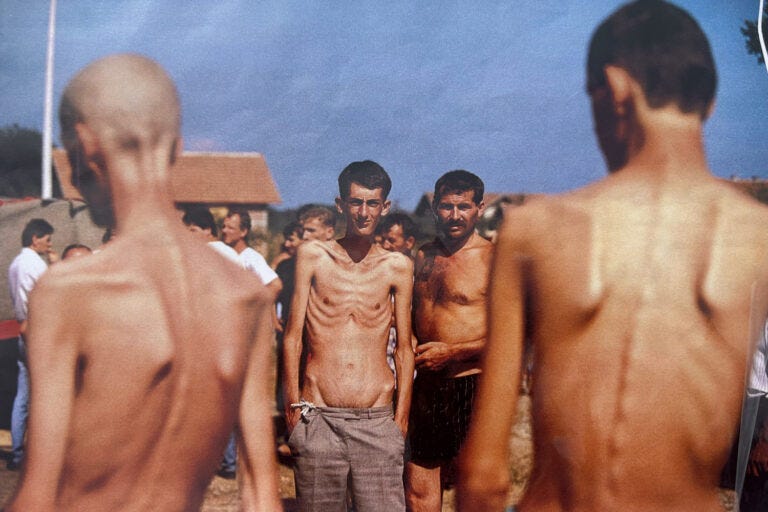

In July 1992, reporters discovered a number of concentration camps in northwestern Bosnia, where Muslims and Croats were being starved, beaten, and tortured. Here is what they found:

And, still, the international community balked—for three years. Instead of directly intervening to stop these war crimes, the Europeans and Americans hesitated.

For the Americans, 1992 was a presidential election year. George H. W. Bush didn’t want to risk American involvement in the Balkans. His secretary of state, James Baker, shrugged that America “didn’t have a dog” in that fight. Luxembourg’s foreign minister Jacques Poos echoed the sentiment, calling Bosnia “the hour of Europe, not the hour of the Americans”—indicating that Europe would respond.

Unfortunately, Europe punted, tossing the matter to the United Nations. Along with the Americans, they succeeded in pushing the UN to deploy peacekeepers to the Balkans—even if those peacekeepers lacked the authority to use force. Worse yet, they imposed an arms embargo to Bosnia, claiming it would prevent an escalation of violence. Instead, it paved the way for Serb destruction—and signaled that the justice and human rights the international community proclaimed to value and uphold existed only on paper—it was nothing more than a talking point.

Some had hoped that Bill Clinton, who took office in 1993, would provide more decisive US action. Yet, Clinton, who had opposed the Vietnam war, heeded the advice of his military advisor. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell resisted American involvement in a conflict that had no clear objectives or exit. Yes, that’s what prompted Madeleine Albright, then the US Ambassador to the UN to ask Powell, “what’s the point of having this superb military…if we can’t use it?” She and Richard Holbrooke, who became the Assistant Secretary for European Affairs during the war, led the charge for the US to stop the carnage, especially after Srebrenica.

The UN declared Srebrenica a “safe area” in 1993. NATO promised air support for UN troops, under a “dual key” system that the UN held. Under “dual key” both the UN’s military commander and the UN’s civilian envoy had to agree to airstrikes. If that wasn’t bureaucratic enough, UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali weighed in to further hamper the process. In July 1995, he, along with the Dutch government, hesitated to bring in NATO to strike the Serbs, who were holding Dutch peacekeepers hostage. The Bosnian Serbs repeatedly kidnapped international soldiers as leverage. Yeah, Ratko Mladić was a motherfucker.

A cable dated July 10, 1995, the day before the Srebrenica massacre began, captures Dutch fears. The embassy in The Hague reported Dutch Defense Minister Voorhoeve’s talk with UN commander General Bernard Janvier. Janvier, had spoken to Bosnian Serb General Mladić and “had received assurances that the Bosnian Serbs had stopped their offensive about a kilometer south of Srebrenica” and that the Bosnian Serbs wouldn’t act further. Neville Chamberlin wasn’t the only foolish world leader.

Though 2.2 million were displaced during the Bosnian war, with nearly 100,000 dead, it was the Srebrenica massacre that shocked everyone into action. NATO began airstrikes against Serb positions. The UN lifted the arms embargo. Both quickly turned the war around, with Muslims and Croats making gains. That motivated the Serbs to sit down to peace talks by the end of the year. (Yes, I’ll get back to that at the end of the year!) In December 1995, the Dayton Peace Accords finally ended the Balkan wars.

Yet, 30 years later, that peace looks increasingly precarious. For the past several years, Bosnian Serb leader Miloran Dodik, has challenged the Dayton framework that split the country into two “entities”—the Republika Srpska and the Federation, in which Muslims and Croats share power. He has talked about secession. Regarding Srebrenica, he denies that it was a genocide. In Just Security, Sead Turčalo notes that denial is a deliberate and well-funded policy that includes rewriting history and hosting protests.

With Ukraine, Sudan, and Gaza in the background, the 30th anniversary of Srebrenica can’t be just another wreath-laying ritual. It should be a reminder that Srebrenica happened because no one wanted to risk political capital to stop unchecked aggression and injustice.—Elmira

Elsewhere in the World.....

On our radar...

Tariffs… They’re baaaacccckkk

After announcing tariffs on April 2, aka “liberation day,” Donald Trump gave a 90-day window for countries to negotiate deals. As that deadline approaches on August 1, it doesn’t look like there will be many worked out. That’s because “trade negotiations are not rapid-fire business deals,” says Inu Manak. “They involve serious and complex diplomacy that engages a broad range of stakeholders, government agencies, and lawmakers.” She notes that trade talks usually take 2.5 years. (CFR)

Israel-Gaza

Yes I did throw up in my mouth when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu presented Donald Trump with a letter nominating him for a Nobel Peace Prize. Netanyahu was in Washington, for a third time since Trump took office in January, supposedly to work out a ceasefire in Gaza. The White House claims it's close to a deal. Tia Goldenberg says that because Israel wants to keep troops in a southern corridor of the Gaza Strip talks might get derailed. (AP)

BRICS meeting

The grouping of non-Western economic powers called BRICS—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—met this week in Rio. Interestingly, notes Natalie Sabanadze, the agenda was not anti-Western. It focused on reforming global governance, advancing the green transition and boosting South-South cooperation. (Chatham House)

US

Apparently, Pete Hegseth authorized a halt on weapons to Ukraine. That was news to Donald Trump, who said he didn’t know anything about it. The US will continue to send weapons to Ukraine and Pete Hegseth will continue to bungle his way through the Pentagon. Let us hope we don’t end up in a nuclear catastrophe. Allison Quinn has more. (The Intelligencer)

Those floods in Texas—the Community Foundation of the Texas Hill Country is supporting NGOs and first responder agencies responding to the tragedy. Here are other ways you can help.

Africa

For weeks, Kenyans have rallied nationwide against police brutality, poor governance, and surging living costs. On the 35th anniversary of the Saba Saba protests—whose pressure ushered in multiparty democracy—the demonstrations turned violent: dozens were killed and more than 100 people were injured. Evelyne Musambi reports. (AP)

Asia

The International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for two top Taliban leaders, for persecuting women and girls, writes Catherine Nicholls. (CNN)

Russia became the first country to recognize the Taliban-led Afghanistan. Will the West follow? Kersten Knipp takes a look. (DW)

In China, Xi Jinping hasn’t been out and about, which has prompted rumors about his health and, even, a growing resistance against his rule. Those aside, what happens if Xi suddenly goes? Mary Gallagher notes that the “opaqueness of China’s political system and its lack of an institutionalized process for political succession are problems with global implications.” (World Politics Review)

The Americas

That “big, beautiful bill” will have implications beyond the US, say Emily Mendrala and Eric Jacobstein. As it impacts immigration and energy policy, Latin America cannot escape its shadow. (Americas Quarterly)

Middle East

Following the 12-day war that Israel started and the US supposedly finished, how do Iran’s leaders move forward—amid degraded military capabilities, damaged nuclear program, and a people increasingly unhappy with its rule? Nicole Grajewski considers the possibilities. (Carnegie Endowment)

Can you bomb nuclear sites without any environmental damage? Jessica McKenzie and Sara Goudarzi consider the direct and indirect impacts of the 12-day war on Iran. (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

Israel and the US say that their attacks on Iran are for the benefit of its women. Iranian feminists couldn’t disagree more, writes Duaa e Zahra Shah. (The Nation)

Europe

French President Emmanuel Macron visited the UK this week, where he and Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced the “one-in-one-out” asylum. Migrants arriving across the English Channel will be returned to France, while the UK will take in asylum seekers who did not try to enter illegally. Sarah Shamim lays out the arrangement. (Al Jazeera)

The two countries will also coordinate on nuclear deterrence.

Since Trump came into office, Europe has been focused on bolstering its defenses. As the war in Ukraine continues, that has meant countries like Germany are building up their armed forces. In fact, Germany is building what will be the largest armed forces in Europe. Given the country’s past, what will that mean? Allison Braden and Liana Fix take a look. (The Signal)

Opportunities

In Dallas, the George W. Bush Institute is hiring for a Managing Director, Global Policy.

In SF, Impact Experience is hiring for an Executive Vice President.

Editorial Team

Elmira Bayrasli - Editor-in-Chief

Thanks for writing this. I remember when I was in 7th grade, a new girl had joined our school. Her name was Dana and she was from Bosnia, a country I had never heard of. I don't know if she had moved to the U.S. because of what happened—she was very shy and I never got to know her, but this would've been around '96 or '97—nor do I know long she had been in the U.S., but in hindsight I wonder if she fled the violence.